Samsung, Korea’s Technological Steward into the Fourth Industrial Revolution

June 6, 2019

Two representatives from Samsung’s renewable energy division began their presentation with a rhetorical question: “What comes to mind when you think of Samsung?” I instantly reached into my pocket and held out my Galaxy S9, and various voices around the room echoed the same word: “Smartphones.” We were dead wrong. Samsung is a much more multi-faceted company than Americans tend to believe, with involvements in the obvious areas smartphone and appliances, as well as batteries, infrastructure, shipbuilding, healthcare, fashion, and energy, to count a few.

Samsung is able to work on such a wide array of projects due to its status as Korea’s largest chaebol. Chaebols are huge, family-owned companies that have a history of close ties with the government. After the devastation brought on by the Korean War, South Korea was forced to rebuild its economy from scratch. Lacking significant natural resources or geographic advantages, the government adopted a strategy of investing heavily in a small number of companies, eliminating competition and propelling them towards success. These companies are known as chaebols, and despite making up only 0.2% of Korean businesses, contribute to 41% of Korea’s GDP. Samsung alone accounts for 17% of the country’s GDP. With a mission statement of “Inspire the world, create the future,” Samsung is set to lead Korea into the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Chaebols are not as unanimously popular as they once were, as well-founded concerns regarding corruption and market manipulation are raised each time executives of chaebols including Samsung, Korean Air, Lotte find themselves at the center of huge scandals. In an effort to give smaller companies a chance in the Korean market, Samsung decided (or was told by the government) to focus its renewable energy development globally, not in Korea. Instead, they focus their efforts overseas to wherever the market is favorable.

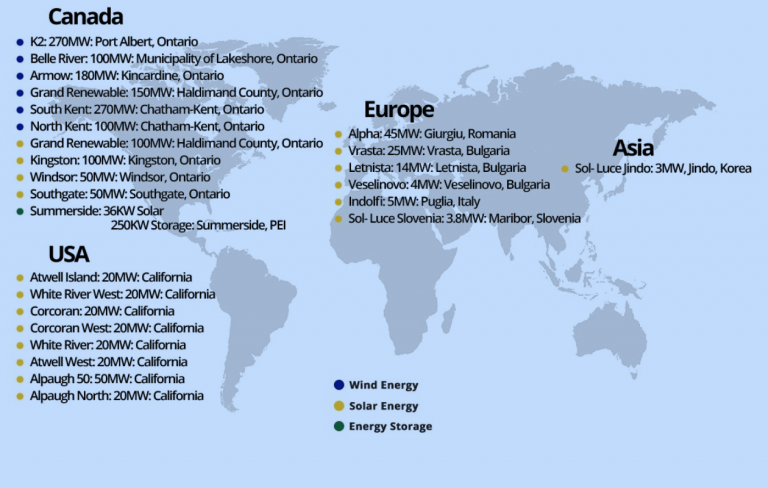

Samsung joined the renewable energy bandwagon late in the game, as they only invested in profitable ventures. They, therefore, had to focus on projects in regions where solar development wasn’t already in place, and the markets were favorable. Samsung initially invested in projects in Eastern European countries such as Romania in order to benefit from huge incentives that these countries had in place. Unfortunately, these projects proved unprofitable, as their governments ran out of funding to follow through on their incentives. Disillusioned with volatile markets, Samsung turned its focus towards areas of North America where solar panel production has been slow, and the state regulations enabled their profit. Current projects are based in Ontario, California, Texas, and Georgia, with several more projects being proposed.

Hearing a for-profit company’s perspective on the merits of renewable energy production gave me a perspective that I hadn’t fully appreciated before the meeting. As a physics major, my experience lies with the implementation, not the economic motivations of renewable technology. With renewable energy portrayed as a political issue in the states, I hadn’t fully wrapped my head around the fact that a company like Samsung could get involved for mostly economic reasons. Samsung thoughtfully observed the emergence of renewables in the West and realized that they could profit by investing in the technologies at strategic times and places. Despite Samsung’s initial troubles in the EU due to the lack of creditworthiness of their host nations, they’ve had an impressive track record in the U.S. and Canada by utilizing various combinations of buying land, installing solar panels, and selling electricity.

Between presentations by the smart city of Songdo, the Korean Development Bank, and Samsung, we’ve been told repeatedly that Korea is positioning itself to be a central participant in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. When asked by one of our students to what degree the Korean government could freely implement infrastructure projects, with the United States and China representing the extremes of bottom-up and top-down approaches respectively, our lecturer from the Iuncheon at the National University coyly responded that Korea was the perfect balance of the two. The chaebol system reflects this approach: while the powerhouse companies in Korea are in fact privately owned, close ties with the government encourage chaebols to work on projects in the interest of the government and the nation. After seeing the incredible economic success that Korea has achieved by using the chaebol system in only sixty years, I’m beginning to believe that this approach really works; Samsung’s dedication seems to truly be towards ensuring the long-term technological success of Korea rather than short-term financial gain, in a way that most private American companies can only feign on their mission statements. If they make the world better by installing solar panels while stewarding Korea’s role in the coming years, then good luck to them.

About the Author

Thomas Richards

ENEC 490H

5/24/2019