UNC capstone students engage Greater Duffyfield residents regarding beloved recreation center

August 1, 2021

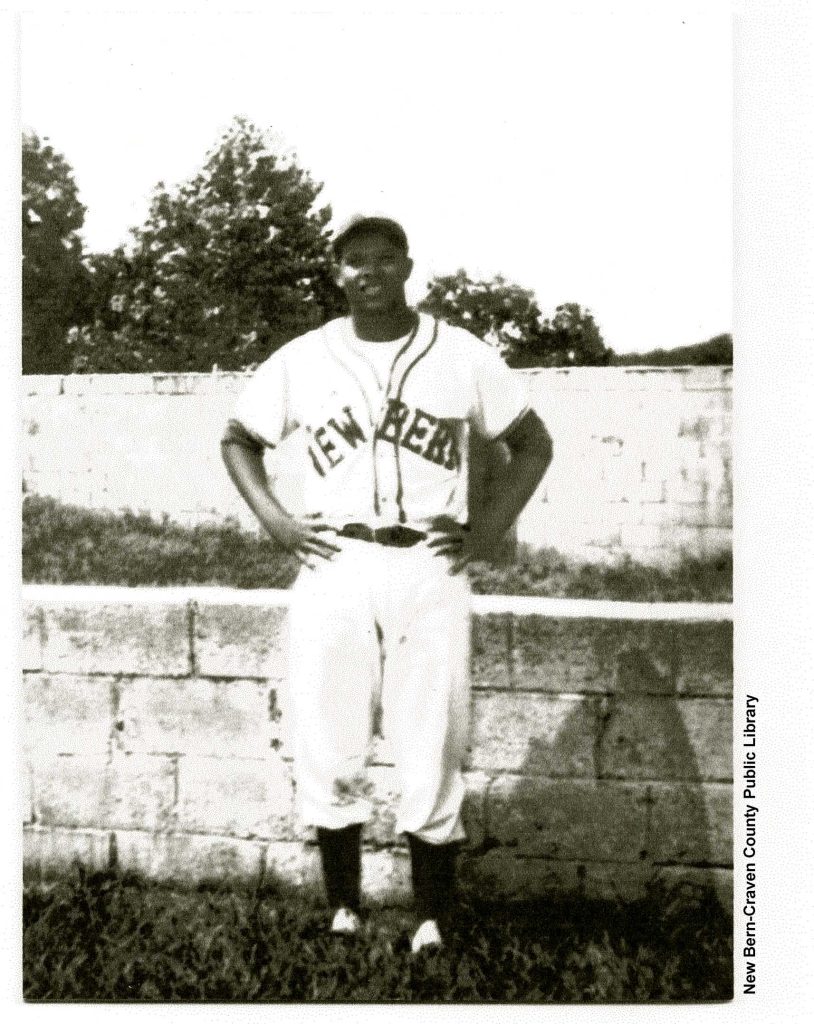

Stanley White dressed in New Bern baseball uniform (Loaned by Cleo White and Pamela White-Holloway to New Bern-Craven County Public Library)

UNC students in one of last semester’s environmental studies capstones sought to help a historically Black community strengthen its resilience to floods while honoring a rich cultural history.

The 12 students in the capstone class worked under the guidance of Professor David Salvesen, director of IE’s Sustainable Triangle Field Site. This program provides an urban field experience where cohort members participate in common courses, seminars, field experiences, internships, and more.

Salvesen’s students worked with the Boys & Girls Club of the Coastal Plain in New Bern, a city on the state’s Eastern Shore. They engaged members of the city’s historically Black Greater Duffyfield community, specifically young people, and sought their feedback on what should be done regarding the Stanley White Recreation Center – which was effectively destroyed by floods from Hurricane Florence.

The recreation center was built at a time when “separate but equal” policies were still legally permissible, so the facility was built specifically for New Bern’s Black community. Although essentially all parties agree that the recreation center should be rebuilt, there is a great deal of controversy regarding its future location.

To honor history or prepare for floods? No clear-cut answer.

The city of New Bern wants to rebuild the recreation center on higher ground a quarter of a mile away from its current location, outside of the historic floodplain that most of Greater Duffyfield lies within, and closer to the city center. This has prompted an outcry from many residents of Greater Duffyfield – a low-income community experiencing disinvestment and abandonment.

“There’s a lot of frustration around this decision and it’s very emotional for the community,” said Georgia Morgan, one of the students who participated in the capstone. “Quite a few folks feel like moving it to this proposed location could make it a more white-facing recreation center, because it faces a white neighborhood and is more on the edge of the Greater Duffyfield community. And there’s also a lot of historical ties to the original location because of the man who the recreation center is named for – Stanley White.”

White was born in New Bern and later became a college athlete, joined the U.S. Army, and eventually served as athletic director at New Bern’s older Cedar Street Recreation Center. He tragically died in 1971 while participating in a baseball game. Building a new recreation center for the community was his dream, and White was remembered for the tremendous positive impact he had on the local Black community – especially its young men, whom he mentored and encouraged to participate in sports and other activities.

Although many older community members want to rebuild the center at the same site, since its location is so full of historical and cultural significance, doing so would be very expensive and likely leave the center vulnerable to more floods.

“FEMA said, basically, ‘We’re not going to pay for you to rebuild a recreation center in a floodplain that’s only going to become more flood-prone over the years as sea levels rise,” Salvesen said.

Salvaging plans amid COVID-19

One segment of Greater Duffyfield’s population, in particular, had not been given many opportunities to voice its opinions on the Stanley White Recreation Center.

“The Boys & Girls Club leadership felt like the youth really hadn’t had a voice in discussions or decisions about the recreation center,” Salvesen said. “And they asked us if we could somehow engage these students in a process where they would learn about issues like hazard mitigation, climate change, sea-level rise, and also have a chance to share with us what they would like to see happen with the new recreation center.”

Thus, the idea for Salvesen’s capstone class was born.

Salvesen teamed up with Frank Lopez, the extension director at North Carolina State University’s North Carolina Sea Grant and the Water Resources Research Institute, for the project in Greater Duffyfield. The pair have known each other since they were in graduate school at UNC and have collaborated on community resilience projects in the past.

“We were kicking around ideas on how we might help communities that have suffered from really severe flooding during Hurricane Florence,” Salvesen said. “And so, we sent out some feelers to some smaller coastal communities, if you will. Our thinking was that smaller communities might not have the resources and the expertise to deal with flood recovery and to recover in a way that reduces their vulnerability to the next storm.”

The pair originally planned a program where 30 to 40 middle and high school students children from the area would come to UNC-Chapel Hill for half a day and learn about flood mitigation, hazard mitigation, sea-level rise, and communication skills.

Salvesen also arranged for a team of all Black female faculty from the UNC drama, geography, and planning departments to present to the students from the Boys & Girls Club. After being fed lunch, the group would be taken to N.C. State University for similar educational sessions focused on urban design and extension.

“All of that was all set to go, literally we were ready to pull the trigger and then the coronavirus hit, and everything came to a rapid halt. And so, the whole project had to be rethought, and we kind of struggled with what we were going to do,” Salvesen said. “And then the Boys & Girls Club leadership said, well, we’ve got a great project for you. We would like our students to be involved in what has been a very controversial decision about the Stanley White Recreation center.”

“The young people and future leaders of the community needed a legitimate platform to voice their concerns and possible solutions on the matter. It was an opportunity to get our Club teens engaged in a project with the capstone students and share a new learning experience,” said Dre’ Nix, chief operating officer of the Boys & Girls Club of the Coastal Plain. “Our teen members got firsthand insight into college work and experiences. The project allowed both groups to learn from each other and better understand the community’s rich history as they navigated the project from start to finish. Club members were proud to see their ideas brought to life in the final project and presentation and give a sense of pride and accomplishment.”

A complex project

Salvesen worked to raise the UNC students’ awareness of issues like hazard mitigation, flooding, and sea-level rise. He also helped them work together as a team to manage a semester-long project, working with middle and high school students. The UNC students did not make recommendations as to where to ultimately place the new recreation center due to the heated controversy surrounding it and the length of time it takes to make such decisions.

“If we got involved with the decision about where to build or relocate the new center – we would never accomplish anything,” Salvesen said. “That’s something that you can’t do in a semester. That’s going to take years and years. Plus, the city had already made up its mind, it seemed, although many members of the community are fighting to change that.

Instead, capstone students explored potential uses for the old recreation center site and recommended ways for the city to improve metaphorical and physical connections between the old and new sites. Their recommendations sought to provide Greater Duffyfield’s residents with ways to strengthen their flood resilience and address their cultural needs, assuming the city rebuilds the recreation center somewhere else – which it seems will likely happen.

As part of the capstone project, UNC students interviewed students from the Boys & Girls Club and surveyed their parents about what they would like to see happen at both the old and new recreation center sites. They also listened to and analyzed comments from public meetings at the recreation center and conducted “key informant” interviews with people who were knowledgeable of the community and willing to share their understanding. Finally, capstone students profiled from around the world several case studies on recreational uses of flood-prone lands.

Their recommendations included building a sunken basketball court at the recreation center’s original site that would double as a facility for holding stormwater during heavy rainfall. They also recommended building rain gardens, bioswales, walking paths composed of permeous surfaces, and man-made water basins and ponds around these paths. These strategies would make the former site an aesthetic place where community members are proud to go, while increasing the area’s resilience to future flooding.

Example of a sunken basketball court in Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Example of a sunken basketball court in Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Students also made recommendations focused on increasing the connectivity between the new and old recreation center sites, such as creating a walking path between the two sites, dotted with educational plaques, bricks, or other signage telling the story of White, the recreation center, or other influential community members.

Other recommendations were made, such as the creation of a community mural or Artspace to illustrate the history of White and the recreation center. Even choices as simple as naming rooms in the new recreation center after revered community members were suggested as ways to honor the residents’ wishes.

Key takeaways for all parties

Salvesen’s students learned many of the skills you would expect from a capstone project – experiential learning, managing a group project, public speaking and preparing and presenting a final report. But most importantly, said Salvesen, they learned how to ask the right questions when working in a disadvantaged community, actively listen, and respect the community’s wishes, rather than assuming that they knew best. Students also learned how to handle a project that lacks the rigid structure of most classroom syllabi.

“One big challenge that all my students struggled with was just figuring out what they were supposed to do,” Salvesen said. “What did the community want? What was the final project going to look like? And working with that kind of uncertainty – and some students might say chaos, initially – is not something that many students are used to doing.”

Morgan said that working with 12 students on an unclear goal was very challenging and pushed her academically. But she also described the process as very rewarding, especially when she spoke with residents of Greater Duffyfield. Morgan was part of the team that conducted Zoom interviews and reached out to community members.

“I got to talk to people and hear firsthand about how much the recreation center means to those folks, what the decision of relocation really means, and what those impacts are. And that was really enlightening to me, and really impactful, and really powerful,” Morgan said. “And I’m glad that I got to be part of that community engagement element because according to these folks, that’s what’s really been missing in the city’s consultant process. It felt really powerful to be part of that for our project. And to hear their feedback and their gratitude during our final presentation kind of made the whole project for me. That made it all worth it – all the challenges and ups and downs.”

Although Morgan said she’s still undecided as to what career path she will pursue, she is interested in local government and community engagement, particularly around sustainability.

Ultimately, Morgan said her experience highlighted the importance of community engagement and its immense challenges. She said she now sees how hard it is for local governments to make everyone happy, but she also recognizes that public decisions are not black-and-white. From her perspective, even the most socially conscious, well-meaning decisions often tell communities what they need rather than asking them what they want.

“It really boils down to who these changes impact and who these facilities are for. I think it’s easy for politicians or people in government to kind of follow through with projects or make decisions and check a box and say, ‘Ooh! Look! This is what I’ve done for the community’ –without really understanding the implications of what those decisions mean for a community,” Morgan said. “And sometimes, through no fault of their own, but we can’t live everyone else’s experience and know. But I think it is a responsibility of local government officials to engage with the community so that they can know what those implications are and those possible consequences.”

As for Salvesen and Lopez, they hope to continue their work in New Bern this coming semester or next year, in a continuation of their longstanding collaborative effort.

“I’m hoping we can have some staying power in the community instead of parachuting in, doing one project for a semester, and leaving. We’d like to make pests of ourselves in the community, I guess. We’d like to stay around for a while,” Salvesen said.

Story by Ellie Heffernan

Ellie Heffernan is a senior at UNC majoring in journalism and environmental studies. During her time at UNC, she has written for The Daily Tar Heel, volunteered with Musical Empowerment as a teacher and leadership team member, and been a part of the Service and Leadership Residential Learning Program.